Can We Really Change Anyone? Some Thoughts for My Activist Friends

I was leading a group during a recent retreat and said something that aroused some wonder. I shared that the most frequent question I used to get when doing lots of keynotes around the world was, “I agree with all you are saying, John, but how can I get (fill in the blank) to change?” Sometimes the blank was their boss, sometimes their team members or co-workers, sometimes the company CEO. All of them could be described as “other than me.”

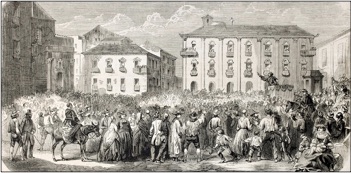

Public orator haranguing a crowd (18th century woodcut)

My standard reply was that I had learned through experience that you can’t change other people. Despite endless and widespread conviction that you can, I have found no evidence that you can change another person. Usually, people have nodded approvingly and I continued my presentation. I suspect now that perhaps it was less approval and more patronizing. However, the response I got from the retreat crowd was more curious, even disagreement, which surprised me some.

One of the men in the group was in the midst of a major campaign to get people involved in reversing a global crisis and had been quite earnest in his commitment to change the hearts and minds of the disengaged. I could see he was being nice to me and not arguing but he wasn’t buying my point of view entirely.

Let me tease this out some so we can examine my stand more closely.

My stand is that for there to be a true change in someone’s psyche or worldview, they must change themselves. Trying to get someone to change can generate a compliant response, pleasing the changer but not doing any real changing internally. This is done is the military, prisons, fraternities, even to a lesser degree in corporate cultures. People can agree to a corporate mission and subscribe to the company’s vision but, as engagement research shows, most of it can be just talk but not walk. Going along to get along.

What we can do to set up an environment where people who want to change find it easier to discover what they want to become. We can also model the change so we become role models and people will seek us out because they want what we have.

But to harangue, preach, coerce or otherwise pressure someone to change doesn’t work.

Think about it in your life. When have you made a real profound change in how you thought or what you believed? When did someone convince you that you needed to change?

Most likely, you changed when you discovered something you didn’t like about the way you were or you recognized an attitude that looked like it worked better than the one you carried around and explored changing yours. Or some tragic event occurred which caused you to do some soul-searching, or a mid-life crisis surfaced some discontent.

This has been my own experience, having lived through dozens of paradigm changes and reframings of my own mental models over the years. Civil Rights Movement, the human potential movement, the women’s movement and the environmental movement are a few of the mindshifts I have experienced.

Before we can effectively co-create environments that allow people who want to change to do so or become role models for how we’d like other people to be, we must first accept others as they are. If we hold them as wrong, or uncaring or stupid, we are very likely to come across that way to them. How would you respond to someone who clearly was unaccepting of your position, attitude or worldview?

For all my colleagues who are heavily invested in changing the hearts and minds of the less-than-active citizens on issues to which they are sincerely committed, let me ask: Might your conviction that you can change people be so deeply held that you are unwilling to examine the underlying assumptions behind your conviction? Might your whole strategy for success be based on a belief that you can change others who may be less enlightened on the issue you care so deeply for? Might your identity as a champion for this cause be getting in the way and working against the very thing you claim to want to see happen?

Humanitarian Lynne Twist states a distinction between a position and a stand:

Taking a position does not create an environment of inclusiveness and tolerance; instead, it creates even greater levels of entrenchment, often by insisting that for me to be right, you must be wrong.

Taking a stand does not preclude you from taking a position. One needs to take a position from time to time to get things done or to make a point. But when a stand is taken it inspires everyone. It elevates the quality of the dialogue and engenders integrity, alignment, and deep trust.

To my activist colleagues, might you be taking a position rather than a stand, which invites the “even greater levels of entrenchment” that Twist writes about?

What frequently occurs is that the “changee” (the person you want to change) adapts a seeming behavior change, perhaps starts talking a different talk, in the hopes of appeasing the “changer” (the person who thinks they can change the other). This often convinces the changer that they were successful when all they got was the pretense of a change, or compliance, not true change at the core of the person’s basic nature.

This “seeming” becomes widespread as more and more people take on the pretense of being different, either to appease their changer or to improve their image as a caring, engaged person.

There are a good number of people pretending to be more enlightened than they are. Perhaps the growing numbers of these pretenders are the results of activists of noble causes trying to convince people they should be more aware and more engaged in social causes.

How ironic? If the attitudes of aggressive change agents generate a reaction of pretense that competes with their own aims they become the primary contributors to the resistance they claim to be wanting to overcome.

I’m reminded of something I saw several years ago on television. A World Wildlife Fund reporter was interviewing a Sudanese farmer about an unwanted local political situation and the farmer responded, “It is very difficult to wake up someone who is pretending to be asleep.”